Read this article in Hawaiian.

At the edge of a forest on the island of O‘ahu, through two massive metal gates—if you can convince someone to let you in—you will find yourself inside the compound of the self-appointed president of the Nation of Hawai‘i.

Dennis Pu‘uhonua Kanahele came to possess this particular 45-acre plot only after a prolonged and extremely controversial occupation, which he led, and which put him in prison for a time, more than three decades ago. Since then, he has built a modest commune on this land, in the shadow of an ancient volcano, with a clutter of bungalows and brightly painted trailers. He’s in his 70s now, and carries himself like an elder statesman. I went to see him because I had, for the better part of 20 years, been trying to find the answer to a question that I knew preoccupied both of us: What should America do about Hawai‘i?

More than a century after the United States helped orchestrate the coup that conquered the nation of Hawai‘i, and more than 65 years since it became a state, people here have wildly different ideas about what America owes the Hawaiian people. Many are fine with the status quo, and happy to call themselves American. Some people even explicitly side with the insurrectionists. Others agree that the U.S. overthrow was an unqualified historic wrong, but their views diverge from that point. There are those who argue that the federal government should formally recognize Hawaiians with a government-to-government relationship, similar to how the United States liaises with American Indian tribes; those who prefer to seize back government from within; and those who argue that the Kingdom of Hawai‘i never legally ceased to exist.

Then there is Kanahele, who has wrested land from the state—at least for the duration of his 55-year lease—and believes other Hawaiians should follow his example. Like many Hawaiians (by which I mean descendants of the Islands’ first inhabitants, who are also sometimes called Native Hawaiians), Kanahele doesn’t see himself as American at all. When he travels, he carries, along with his U.S. passport, a Nation of Hawai‘i passport that he and his followers made themselves.

But outside the gates of his compound, there is not only an American state, but a crucial outpost of the United States military, which has 12 bases and installations here—including the headquarters for U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and the Pacific Missile Range Facility. The military controls hundreds of thousands of acres of land and untold miles of airspace in the Islands.

It seems unrealistic, to say the least, to imagine that the most powerful country in the world would simply give Hawai‘i back to the Hawaiians. If it really came down to it, I asked, how far would Kanahele go to protect his people, his nation? That’s a personal question, Kanahele told me. “That’s your life, you know. What you’re willing to give up. Not just freedom but the possibility to be alive.”

Sitting across the table from us, his vice president, Brandon Maka‘awa‘awa, conceded that there had, in the past, been moments when it would have been easy to choose militancy. “We could have acted out of fear,” he said. But every time, they “acted with aloha and we got through, just like our queen.” He was referring to Hawai‘i’s last monarch, Queen Lili‘uokalani, who was deposed in the coup in 1893.

People tend to treat this chapter in U.S. foreign relations as a curiosity on the margins of history. This is a mistake. The overthrow of Hawai‘i is what established the modern idea of America as a superpower. Without this one largely forgotten episode, the United States may never have endured an attack on Pearl Harbor, or led the Allies to victory in World War II, or ushered in the age of Pax Americana—an age that, with Donald Trump’s return to power, could be coming to an end.

Some Hawaiians see what is happening now in the United States as a bookend of sorts. In their view, the chain of events that led to a coup in Hawai‘i in 1893 has finally brought us to this: the moment when the rise of autocracy in America presents an opportunity for Hawaiians to extricate themselves from their long entanglement with the United States, reclaim their independence, and perhaps even resurrect their nation.

Keanu Sai is, today, one of the more extreme thinkers about Hawaiian sovereignty. Growing up in Kuli‘ou‘ou, on the east end of O‘ahu, Sai was a self-described slacker who only wanted to play football. He graduated from high school in 1982 and went straight to a military college, then the Army.

In 1990, he was at Fort Sill, in Oklahoma, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, annexing it as Iraq’s 19th province. International condemnation was swift; the United Nations Security Council declared the annexation illegal. An American-led coalition quickly beat back Saddam, liberating Kuwait. “And that’s when I went, Wait a minute. That’s exactly what happened” in Hawai‘i, Sai told me. “Our government was overthrown.” The idea radicalized him.

Before Hawai‘i’s overthrow, it had been a full-fledged nation with diplomatic relationships across the globe and a modern form of governance (it also signed a peace treaty with the United States in 1826). As a constitutional monarchy, it had elected representatives, its own supreme court, and a declaration of rights modeled after the U.S. Bill of Rights. And, as people in Hawai‘i like to remind outsiders, ‘Iolani Palace had electricity before the White House did.

Then, in January 1893, a group of 13 men—mostly Americans or Hawai‘i-born businessmen descended from American missionary families, all with extensive financial interests in the Islands—executed a surprise coup. They did so with remarkable speed and swagger, even by coup standards. The men behind the effort referred to themselves as the Committee of Safety (presumably in a nod to the American and French Revolutions) and had good reason to expect that they would succeed: They had the backing of the U.S. foreign minister to the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, John L. Stevens, who called up a force of more than 160 Marines and sailors to march on Honolulu during the confrontation with the queen. Stevens later insisted that he had done so in a panic—a coup was unfolding! It was his duty to do whatever was necessary to protect American lives and property! A good story, but not a convincing one.

Months before the coup, Stevens had written a curious letter to his friend James Blaine, the U.S. secretary of state, in which he’d posed a bizarre and highly detailed hypothetical: What if, Stevens had wanted to know, the government of Hawai‘i were to be “surprised and overturned by an orderly and peaceful revolutionary movement” that established its own provisional government to replace the queen? If that were to happen, Stevens pressed, just how far would he and the American naval commander stationed nearby be permitted to “deviate from established international rules” in their response? The presence of U.S. Marines, Stevens mused, might be the only thing that could quash such an overthrow and maintain order. As it turned out, however, Stevens and his fellow insurrectionists used the Marines to ensure that their coup would succeed. (Blaine, for his part, had had his eye on the Islands for decades.) Two weeks after the overthrow, Stevens wrote to John W. Foster, President Benjamin Harrison’s final secretary of state: “The Hawaiian pear is now fully ripe, and this is the golden hour for the United States to pluck it.”

Queen Lili‘uokalani had yielded immediately to the insurrectionists, unsure whether Stevens was following orders from Harrison. “This action on my part was prompted by three reasons,” she wrote in an urgent letter to Harrison: “the futility of a conflict with the United States; the desire to avoid violence, bloodshed, and the destruction of life and property; and the certainty which I feel that you and your government will right whatever wrongs may have been inflicted on us in the premises.”

Her faith in Harrison was misplaced; he ignored her letter. In the last month of his presidency, he sent a treaty to the U.S. Senate to advance the annexation of Hawai‘i to the United States. (Lorrin A. Thurston, one of the overthrow’s architects, boasted in his Memoirs of the Hawaiian Revolution that in early 1892, Harrison had encouraged him, through an interlocutor, to go forward with his plot.)

Looking back at this history nearly 100 years later, Keanu Sai had an epiphany. “I was in the wrong army,” he said. Sai left the military and dove into the state archives, researching Hawai‘i’s history and his own family’s lineage prior to the arrival of haole (white) Europeans and Americans. He says he traced his family’s roots to ali‘i, members of Hawai‘i’s noble class. “I started to realize that the Hawaiian Kingdom that I was led to believe was all haole-controlled, missionary-controlled, was all—pardon the French—bullshit,” he told me.

That led him to develop what is probably the most creative, most radical, and quite possibly most ridiculous argument about Hawaiian independence that I’ve ever heard. Basically, it’s this: The Hawaiian Kingdom never ceased to exist.

Though Sai has plenty of fans and admirers, several people warned me that I should be careful around him. I spoke with some Hawaiians who expressed discomfort with the implications of Sai’s notion that the kingdom was never legally dissolved—not everyone wants to be a subject in a monarchy. There was also the matter of his troubles with the law.

In 1997, Sai took out an ad in a newspaper declaring himself to be a regent of the Hawaiian Kingdom, a move that he said formally entrusted him “with the vicarious administration of the Hawaiian government during the absence of a Monarch.” He had started a business in which he and his partner charged people some $1,500 for land-title research going back to the mid-19th century, promising to protect clients’ land from anyone who might claim it as their own. The business model was built on his theory of Hawaiian history, and the underlying message seemed to be: If the kingdom still exists, and the state of Hawai‘i does not, maybe this house you bought isn’t technically even yours. Ultimately, Sai’s business had its downtown office raided; the title company shut down, and he was convicted of felony theft.

It struck me that, in another life, Keanu Sai would have made a perfect politician. He is charismatic and funny. A decorated bullshit artist. Unquestionably smart. Filibusters with the best of them. (He also told me that Keanu Reeves is his cousin.) Although Sai’s methods may be questionable, his indignation over the autocratic overthrow of his ancestors’ nation is justified.

Sai says that arguments about Hawaiian sovereignty tend to distort this history. “They create the binary of colonizer-colonized,” he said. “All of that is wrong. Hawai‘i was never a colony of the United States. And we’re not a tribal nation similar to Native Americans. We’re nationals of an occupied state.”

Following this logic, Sai believes international courts must acknowledge that America has perpetuated war crimes against Hawai‘i’s people. After that, he says, international law should guide Hawai‘i out of its current “wartime occupation” by the United States, so that the people of Hawai‘i can reconstruct their nation. Sai has attempted to advance this case in the international court system. So far, he has been unsuccessful.

At one point, Sai mused that I’d have to completely rework my story based on his revelations. I disagreed, but said that I liked hearing from him about this possible path to Hawaiian independence. This provoked, for the first time in our several hours of conversations, a flash of anger. “This is not the ‘possible path,’ ” Sai said. “It is the path.”

The island of Ni‘ihau is just 18 miles long and six miles wide. Nicknamed “the forbidden island,” it has been privately owned since 1864, when King Kamehameha IV and his brother sold it for $10,000 in gold to a wealthy Scottish widow, Elizabeth Sinclair, who had moved her family to Hawai‘i after her husband and son were lost at sea.

Sinclair’s descendants still own and run the island, which by the best estimates has a population of fewer than 100. It is the only place in the world where everyone still speaks Hawaiian. No one is allowed to visit Ni‘ihau without a personal invitation from Sinclair’s great-great-grandsons Bruce and Keith Robinson, both now in their 80s. Such invitations are extraordinarily rare. (One of the two people I know who have ever set foot on Ni‘ihau got there only after asking the Robinsons every year for nearly 10 years.)

The island has no paved roads, no electrical grid, no street signs, and no domestic water supply—drinking water comes from catchment water and wells. In the village is a schoolhouse, a cafeteria, and a church, which everyone is reportedly expected to attend. One of the main social activities is singing. The rules for Ni‘ihau residents are strict: Men cannot wear their hair long, pierce their ears, or grow beards. Drinking and smoking are not allowed. The Robinsons infamously bar anyone who leaves for even just a few weeks from returning, with few exceptions.

Ni‘ihau’s circumscribed mores point to a broader question: If one goal of Hawaiian independence is to restore a nation that has been lost, then which version of Hawai‘i, exactly, are you trying to bring back?

Ancient explorers first reached the archipelago in great voyaging canoes, traveling thousands of miles from the Marquesas Islands, around the year 400 C.E. They brought with them pigs, chickens, gourds, taro, sugarcane, coconuts, sweet potatoes, bananas, and paper mulberry plants. Precontact Hawai‘i was home to hundreds of thousands of Hawaiians—some scholars estimate that the population was as high as 1 million. There was no concept of private land ownership, and Hawaiians lived under a feudal system run by ali‘i, chiefs who were believed to be divinely ordained. This strict caste system entailed severe rules, executions for those who broke them, and brutal rituals including human sacrifice.

The first British explorers moored their ships just off the coast of Kaua‘i in 1778 and immediately took interest in the Islands. Captain James Cook, who led that first expedition, was welcomed with aloha by the Hawaiian people. But when Cook attempted to kidnap the Hawaiian chief Kalani‘ōpu‘u on a subsequent visit to the Islands, a group of Hawaiians stabbed and bludgeoned Cook to death. (Kalani‘ōpu‘u survived.)

Eventually, fierce battles culminated in unification of all the Islands under Hawai‘i’s King Kamehameha, who finally conquered the archipelago’s last independent island in 1810. The explosion and subsequent collapse of the sandalwood trade followed, along with the construction of the first sugar plantations and the arrival of whaling ships. Missionaries came too, and the introduction of Christianity led, for a time, to a ban on the hula—one of the Hawaiian people’s most sacred and enduring forms of passing down history. All the while, several waves of epidemics—cholera, mumps, measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, smallpox, and bubonic plague—ravaged the Hawaiian population, which plummeted to about 40,000 by the end of the 19th century.

During this period, the United States had begun to show open interest in scooping up the Sandwich Islands, as they were then called. In the June 1869 issue of The Atlantic, the journalist Samuel Bowles wrote:

We have converted their heathen, we have occupied their sugar plantations; we furnish the brains that carry on their government, and the diseases that are destroying their people; we want the profit on their sugars and their tropical fruits and vegetables; why should we not seize and annex the islands themselves?

Elizabeth Sinclair’s descendants profited greatly from the sugar they cultivated, but they had a different view of what Hawai‘i should be. King Kamehameha IV is said to have sold Ni‘ihau on one condition: Its new owners had to promise to do right by the Hawaiian people and their culture. This is why, when the United States did finally move to “seize and annex the islands,” the Robinsons supported the crown. After annexation happened anyway, in 1898, Sinclair’s grandson closed Ni‘ihau to visitors.

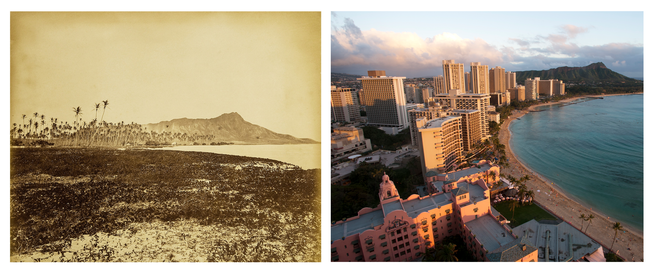

On the other islands, everything seemed to speed up from there. Schools had already banned the Hawaiian language, but now many Hawaiian families started speaking only English with their children. The sugar and pineapple industries boomed. Matson ships carrying visitors to Hawai‘i soon gave way to airplanes. As exoticized ideas about Hawaiian culture spread, repackaged for tourists, Hawaiianness was suppressed nearly to the point of erasure.

Through all of this, Ni‘ihau stayed apart. History briefly intruded in 1941, when a Japanese fighter pilot crash-landed there hours after participating in the attack on Pearl Harbor, which killed an estimated 2,400 people in Honolulu. Ni‘ihau residents knew nothing about the mayhem of that day. They at first welcomed the Imperial pilot as a guest, but killed him after he botched an attempt to hold some of them hostage.

If the overthrow had marked the beginning of the end of Hawaiian nationhood, the attack on Pearl Harbor finished it. It also kicked off a three-year period of martial law in Hawai‘i, in which the military took control of every aspect of civilian life—in effect converting the Islands into one big internment facility. The government suspended habeas corpus, shut down the courts, and set up its own tribunals for law enforcement. The military imposed a strict nightly curfew, rationed food and gasoline, and censored the press and other communications. The many Japanese Americans living there were surveilled and treated as enemies—Japanese-run banks were shut down, along with Japanese-language schools. Everyone was required to carry identification cards, and those older than the age of 6 were fingerprinted. Telephone calls and photography were restricted. Sugarcane workers who didn’t report to their job could be tried in military court.

Martial law was fully lifted in 1944, and in 1959, Hawai‘i became the 50th state—a move the Robinsons are said to have opposed. But whether they liked it or not, statehood dragged Ni‘ihau along with it. The island is technically part of Kaua‘i County, the local government that oversees the island closest to it. Still, Ni‘ihau has stayed mostly off-limits to the rest of Hawai‘i and the rest of the world. (The Robinsons do operate a helicopter tour that takes visitors to an uninhabited beach on the far side of the island, but you can’t actually get to the village or meet any residents that way.) Those who have affection for Ni‘ihau defend it as an old ranch community on a remote island that’s not hurting anybody. The less generous view is that it’s essentially the world’s last remaining feudal society.

But no one is arguing that the rest of Hawai‘i should be run like Ni‘ihau. After all, the entire goal of the sovereignty movement, if you can even say it has a single goal, is to confer more power on the Hawaiian people, not less. The question is how best to do that.

John Waihe‘e’s awakening came the summer before he started seventh grade, when he checked a book out of the library in his hometown of Honoka‘a, on the Big Island, that would change his life. In it, he read a description of the annexation ceremony that had taken place at ‘Iolani Palace in 1898, when Hawai‘i officially became a territory of the United States. It described the lowering of the Hawaiian flag, and the Hawaiian people who had gathered around with tears in their eyes.

This was the 1950s—post–Pearl Harbor and pre-statehood—and Waihe‘e had never even heard of the overthrow. His parents spoke Hawaiian with each other at home, but never spoke it with Waihe‘e.

“I remember rushing back to my father and telling him, ‘Dad, I didn’t know any of this stuff,’ ” Waihe‘e told me. “He looks at me, and he was very calm about it. He said, ‘You know, son, that didn’t only happen in Honolulu.’ ” His father went on: “They lowered the flag in Hilo too, on the Big Island, and your grandfather was there, and he saw all of this. ”

Waihe‘e was floored. Even nearly 70 years later, he remembers the moment. To picture his grandfather among those watching the kingdom in its final hours “broke my heart,” he said. Waihe‘e had never met his grandfather, but he had seen photos and heard stories about him all his life. “He was this big, strong Hawaiian guy. And the idea of him crying was—it was unthinkable.” The image never left him. He grew up, attended law school, and eventually became Hawai‘i’s governor in 1986, the first Hawaiian ever to hold the office.

Waihe‘e is part of a class of political leaders in Hawai‘i who have chosen to work within the system, rather than rail against it. Another was the late Daniel Akaka, one of Hawai‘i’s longest-serving U.S. senators— a Hawaiian himself. Akaka was raised in a home where he was not permitted to speak Hawaiian. He once told me about hearing a roar from above on the morning of December 7, 1941, and looking up to see a gray wave of Japanese bombers with bright-red dots on the wings. He grabbed his rifle and ran into the hills. He was 17 then, and would later deploy to Saipan with the Army Corps of Engineers.

In 1993, Akaka, a Democrat, sponsored a joint congressional resolution that formally apologized to the Hawaiian people for the overthrow of their kingdom 100 years earlier and for “the deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination.” I’d always seen the apology bill, which was signed into law by President Bill Clinton, as an example of the least the United States could possibly do, mere lip service. But the more people I talked with as I reported this story, the more I heard that it mattered—not just symbolically but legally.

Recently, I went to see Esther Kia‘āina, who was one of the key architects of the apology as an aide to Akaka in Washington, D.C., in the early 1990s. Today, Kia‘āina is a city-council member in Honolulu. People forget, she told me, just how hard it was to get to an apology in the first place.

“Prior to 1993, it was abysmal,” Kia‘āina said. There had been a federal inquiry into the overthrow, producing a dueling pair of reports in the 1980s, one of which concluded that the U.S. bore no responsibility for what had happened to Hawai‘i, and that Hawaiians should not receive reparations as a result. Without the United States first admitting wrongdoing, Kia‘āina said, nothing else could follow. As she saw it, the apology was the first in a series of steps. The next would be to obtain official tribal status for Hawaiians from the Department of the Interior, similar to the way the United States recognizes hundreds of American Indian and Alaska Native tribes. Then full-on independence.

In the early 2000s, Akaka began pushing legislation that would create a path to federal recognition for Hawaiians as a tribe, a move that Kia‘āina enthusiastically supported. “I was Miss Fed Rec,” she said. It wasn’t a compliment—lots of people hated the idea.

The federal-recognition legislation would have made Native Hawaiians one of the largest tribes in America overnight—but many Hawaiians didn’t want recognition from the United States at all. The debate created strange bedfellows. Many people argued against it on the grounds that it didn’t go far enough; they wanted their country back, not tribal status. Meanwhile, some conservatives in Hawai‘i, who tended to be least moved by calls for Hawaiian rights, fought against the bill, arguing that it was a reductionist and maybe even unconstitutional attempt to codify preferential treatment on the basis of race. That’s how a coalition briefly formed that included Hawaiian nationalists and their anti-affirmative-action neighbors.

Akaka’s legislation never passed, and the senator died in 2018. Today, some people say the debate over federal recognition was a distraction, but Kia‘āina still believes that it’s the only way to bring about self-determination for Hawaiians. She told me that she sometimes despairs at what the movement has become: She sees people rage against the overthrow, and against the continued presence of the U.S. military in Hawai‘i, but do little else to promote justice for Hawaiians. And within government, she sees similar complacency.

“It’s almost like ‘Are you kidding me? We give you the baton and this is what you do?’ ” Kia‘āina said. Instead of effecting change, she told me, people playact Hawaiianness and think it will be enough. They “slap on a Hawaiian logo,” and “that’s your contribution to helping the Hawaiian community.” And in the end, nobody outside Hawai‘i is marching in the street, protesting at the State Department, or occupying campus quads for Native Hawaiians.

There is no question that awareness of Hawaiian history and culture has improved since the 1970s, a period that’s come to be known as the Hawaiian Renaissance, when activists took steps to restore the Hawaiian language in public places, to teach hula more widely, and to protect and restore other cultural practices. But Kia‘āina told me that although the cultural and language revival is lovely, and essential, it can lull people into thinking that the work is done when plainly it is not. Especially when Hawaiians are running out of time.

Sometime around 2020, the Hawaiian people crossed a terrible threshold. For the first time ever, more Hawaiians lived outside Hawai‘i than in the Islands. Roughly 680,000 Hawaiians live in the United States, according to the most recent census data; some 300,000 of them live in Hawai‘i.

Hawaiians now make up about 20 percent of the state population, a proportion that for many inspires existential fear. Meanwhile, outsiders are getting rich in Hawai‘i, and rich outsiders are buying up Hawaiian land. Larry Ellison, a co-founder of Oracle, owns most of the island of Lāna‘i. Facebook’s co-founder Mark Zuckerberg owns a property on Kaua‘i estimated to be worth about $300 million. Salesforce’s CEO, Marc Benioff, has reportedly purchased nearly $100 million worth of land on the Big Island. Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, reportedly paid some $80 million for his estate on Maui. As one longtime Hawai‘i resident put it to me: The sugar days may be over, but Hawai‘i is still a plantation town.

At the same time, many Hawaiians are faring poorly. Few have the means to live in Hawai‘i’s wealthy neighborhoods. On O‘ahu, a commute to Waikīkī for those with hotel or construction jobs there can take hours in island traffic. Hawaiians have among the highest rates of heart disease, hypertension, asthma, diabetes, and some types of cancer compared with other ethnic groups. They smoke and binge drink at higher rates. A quarter of Hawaiian households can’t adequately feed themselves. More than half of Hawaiians report worrying about having enough money to keep a roof over their head; the average per capita income is less than $28,000. Only 13 percent of Hawaiians have a college degree. The poverty rate among Hawaiians is 12 percent, the highest of the five largest ethnic groups in Hawai‘i. Although Hawaiians make up only a small percentage of the population in Hawai‘i, the share of homeless people on O‘ahu who identify as Hawaiian or Pacific Islander has hovered at about 50 percent in recent years.

Kūhiō Lewis was “very much the statistic Hawaiian” growing up in the 1990s, he told me—a high-school dropout raised by his grandmother. He’d struggled with drugs and alcohol, and became a single father with two babies by the time he was 19. Back then, Lewis was consumed with anger over what had happened to the Hawaiian people and believed that the only way to get what his people deserved was to fight, and to protest. But he lost patience with a movement that he didn’t think was getting anything done. Today, as the CEO of the nonprofit Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement, he has a different view.

He still believes that Hawai‘i should not be part of America, but he also believes that Hawai‘i would need a leader with “balls of steel” to make independence happen. “That’s a big ask,” he added. “That’s a lot of personal sacrifice.” Until that person steps up, Lewis chooses to work within the system, even if it means some Hawaiians see him as a sellout.

“There is a wrong that was done. And there’s no way we’ll ever let that go,” Lewis told me. “But I also believe, and I’ve come to believe, that the best way to win this battle is going through America rather than trying to go around America.”

When I spoke with Brian Schatz, Hawai‘i’s senior senator, in Washington, he said he is most focused on addressing the moment-to-moment crisis for the Hawaiian people. Lots of Native Hawaiians, he said, “are motivated by the same set of issues that non-Native Hawaiians are motivated by. They don’t wake up every morning thinking about sovereignty and self-determination. They wake up every morning thinking about the price of gasoline, and traffic, and health care.” He went on: “They are deeply, deeply uninterested in a bunch of abstractions. They would rather have a few hundred million dollars for housing than some new statute that purports to change the interaction between America and Hawaiians.”

Ian Lind, a former investigative reporter who is himself Hawaiian, is also critical of sovereignty discussions that rely too much on fashionable ideologies at the expense of reality. I’ve known Lind since my own days as a city-hall reporter in Honolulu, in the early 2000s, and I wanted to get his thoughts on how the sovereignty conversation had changed in the intervening years. He told me that, in his view, an “incredibly robust environment for charlatans and con artists” has metastasized within Hawaiian-sovereignty circles. There are those who invent royal lineage or government titles for themselves, as well as ordinary scammers.

Even those who are merely trying to understand—or in some cases teach—the history have become too willing to gloss over some subtleties, Lind told me. It’s not so simple to say that Hawaiians were dispossessed at the time of the overthrow, that they suddenly lost everything, he said. Many people gave up farmlands that had been allotted to them after the Great Māhele land distribution in 1848. “They were a burden, not an asset,” Lind said. “People thought, I could just go get a job downtown and get away from this.”

But people bristle at the introduction of nuance in the telling of this history, partly because they remain understandably focused on the immensity of what Hawaiians have lost. “There’s a faction of Hawaiians who say that absolutely nothing short of restoring a kingdom like we had before, encompassing all of Hawai‘i, is going to suffice,” Lind said. “It’s like an impasse that no one wants to talk about.”

The whole thing reminds Lind of a fringe militia or a group of secessionists you’d find elsewhere. “It’s so much like watching the Confederacy,” he said. “You’re watching something, a historical fact, you didn’t like. It wasn’t your side that won. But governments changed. And when our government changed here, it was recognized by all the countries in the world very quickly. So whatever you want to think about 130 years ago, how you feel about that change, I just think there are so many more things to deal with that could be dealt with now realistically that people aren’t doing, because they’re hung up waving the Confederate flag or having a new, reinstated Hawaiian Kingdom.”

When you talk with people in Hawai‘i about the question of sovereignty, skeptics will say shocking things behind closed doors, or off the record, that they’d never say in public—I’ve encountered eye-rolling, a general sentiment of get over it, even disparaging Queen Lili‘uokalani as an “opium dealer”—but invoking the Lost Cause this way was a new one for me. I asked Lind if his opinions have been well received by his fellow Hawaiians. “No,” he said with a chuckle. “I’m totally out of step.”

Brian Schatz, a Democrat, grew up on O‘ahu before making a rapid ascent in local, then national, politics. I first met him more than 15 years ago, when he was coming off a stint as a state representative. In 2021, he became the chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, meaning he thinks about matters related to Indigenous self-determination a lot. He’s also on the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, which makes sense for a person representing a region of profound strategic importance to the United States.

Because Schatz is extremely online—he is a bit of a puppy dog on X, not exactly restrained—I wanted to know his views on an observation I’ve had in recent years. As young activists in Hawai‘i have focused their passion on justice for Hawaiians, I’ve sometimes wondered if they are simply shouting into the pixelated abyss. On the one hand, more awareness of historical wrongs is objectively necessary and good. On the other, as Schatz put it to me, “the internet is not a particularly constructive place to figure out how to redress historical wrongs.”

Two recent moments in Hawaiian activism sparked international attention, but haven’t necessarily advanced the cause of self-determination. In 2014, opposition to the construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope on the Big Island led to huge protests, and energized the sovereignty movement. The catastrophic fires on Maui in 2023 prompted a similar burst of attention to Hawai‘i and the degree to which Hawaiians have been alienated from their own land. But many activists complained to me that in both cases, sustained momentum has been spotty. Instagrammed expressions of solidarity may feel righteous when you’re scrolling, but they accomplish little (if anything) offline, even when more people than ever before seem to be paying attention to ideas that animate those fighting for Hawaiian independence.

“There’s a newly energized cohort of leftists on the continent who are waking up to this injustice,” Schatz said. “But, I mean, the truth is that there’s not a place on the continental United States where that story wasn’t also told.” The story he’s talking about is the separation of people from their language, their land, their culture, and their water sources, in order to steal that land and to make money. Yet “nobody’s talking about giving Los Angeles back,” he said.

One of the challenges in contemplating Hawaiian independence is the question of historical precedent. Clearly there are blueprints for decolonization—India’s independence following British rule may be the most famous—but few involve places like Hawai‘i. The world does not have many examples of what “successful” secession or decolonization from the United States looks like in practice. There is one example from elsewhere in the Pacific: In 1898, fresh off its annexation of Hawai‘i, the United States moved to annex the Philippines, too. People there fought back, in a war that led to the deaths of an estimated 775,000 people, most of them civilians. The United States promised in 1916 that it would grant the Philippines independence, but that didn’t happen until 1946.

Hawai‘i is particularly complex, too, because of its diverse population. Roughly a quarter of Hawai‘i residents are multiracial, and there is no single racial majority. So while some activists are eager to apply a settler-colonialism frame to what happened in Hawai‘i, huge populations of people here do not slot neatly into the categories of “settler” or “native.” How, for example, do you deal with the non-Hawaiian descendants of laborers on plantations, who immigrated to the Islands from China, Japan, Portugal, the Philippines? Or the Pacific Islanders who came to Hawai‘i more recently, as part of U.S. compensation to three tiny island nations affected by nuclear-weapons testing? Or the people who count both overthrowers and Hawaiians among their ancestors? Schatz said that when it comes to visions of Hawaiian self-determination, “I completely defer to the community.”

But he cautioned that without consensus about what this should look like, “the danger is that we spend all of our time counting the number of angels on the head of a pin, and ignore the fact that the injustice imposed by the United States government on Native Hawaiians is manifesting itself on a daily basis with bad economic outcomes, not enough housing, not enough health care.” He went on, “So while Native Hawaiian leaders and scholars sort out what comes next as it relates to Native Hawaiians and their relationship to the state and federal government, my job is to—bit by bit, program by program, day by day—try to reverse that injustice with, frankly, money.

“Because you can’t live in an apology,” he added. “You have to live in a home.”

The question of how the ancient Hawaiians survived—how they managed to feed a complex civilization that bloomed on the most isolated archipelago on the planet—has long been a source of fascination and historic inquiry. They fished; they hunted; they grew taro in irrigated wetlands.

Hawai‘i is now terrifyingly dependent on the global supply chain for its residents’ survival. By the 1960s, it was importing roughly half of its food supply. Today, that figure is closer to 90 percent. It can be easy to forget how remote Hawai‘i truly is. But all it takes is one hurricane, war, or pandemic to upset this fragile balance.

To understand what Hawai‘i would need in order to become self-reliant again, I went to see Walter Ritte, one of the godfathers of modern Hawaiian activism, and someone most people know simply as “Uncle Walter.” Ritte made a name for himself in the 1970s, when he and others occupied the uninhabited island of Kaho‘olawe, protesting the U.S. military’s use of the land for bombing practice. Ian Lind was part of this protest too; the group came to be known as the Kaho‘olawe Nine.

Ritte lives on Moloka‘i, among the least populated of the Hawaiian Islands. Major airlines don’t fly to Moloka‘i, and people there like it that way. I arrived on a turboprop Cessna 208, a snug little nine-seater, alongside a few guys from O‘ahu heading there to do construction work for a day or two.

Moloka‘i has no stoplights and spotty cell service. Its population hovers around 7,000 people. Many of its roads are still unpaved and require an off-road vehicle—long orange-red ribbons of dirt crisscross the island. On one particularly rough road, I felt my rented Jeep keel so far to one side that I was certain it would tip over. I considered turning back but eventually arrived at the Mo‘omomi Preserve, in the northwestern corner of Moloka‘i, where you can stand on a bluff of black lava rock and look out at the Pacific.

All over Moloka‘i, the knowledge that you are standing somewhere that long predates you and will long outlast you is inescapable. If you drive all the way east, to Hālawa Valley, you find the overgrown ruins of sacred places—an abandoned 19th-century church, plus remnants of heiau, or places of worship, dating back to the 600s. The desire to protect the island’s way of life is fierce. Nobody wants it to turn into O‘ahu or Maui—commodified and overrun by tourists, caricatured by outsiders who know nothing of this place. For locals across Hawai‘i, especially the large number who work in the hospitality industry, this reality is an ongoing source of fury. As the historian Daniel Immerwahr put it to me: “It is psychologically hard to have your livelihood be a performance of your own subordination.”

The directions Ritte had given me were, in essence: Fly to Moloka‘i, drive east for 12 miles, and look for my fishpond. So I did. Eventually, I stopped at a place that I thought could be his, a sprawling, grassy property with some kukui-nut trees, a couple of sheds, and a freshwater spring. No sign of Ritte. But I met a man who introduced himself as Ua and said he could take me to him. I asked Ua how long he’d been working with Uncle Walter, and he grinned. “My whole life,” he said. Walter is his father.

Ua drove us east in his four-wheeler through a misty rain. This particular vehicle had a windshield but no wipers, so I assumed the role of leaning all the way out of the passenger side to squeegee water off the glass.

We found Ritte standing in a field wearing dirty jeans and a black T-shirt that said Kill Em’ With Aloha. Ritte is lean and muscular—at almost 80 years old, he has the look of someone who has worked outside his whole life, which he has. We decided to head makai, back toward the ocean, so Ritte could show me his obsession.

When we got there, he led me down a short, rocky pier to a thatched-roof hut and pointed out toward the water. What we were looking at was the rebuilt structure of a massive fishpond, first constructed by ancient Hawaiians some 700 years ago. Ritte has been working on it forever, attempting to prove that the people of Hawai‘i can again feed themselves.

The mechanics of the pond are evidence of Native Hawaiian genius. A stone wall serves as an enclosure for the muliwai, or brackish, area where fresh and salt water meet. A gate in the wall, when opened, allows small fish to swim into the muliwai but blocks big fish from getting out. And when seawater starts to pour into the pond, fish already in the pond swim over to it, making it easy to scoop them out. “Those gates are the magic,” Ritte tells me.

Back when Hawai‘i was totally self-sustaining, feeding the population required several fishponds across the Islands. Ritte’s fishpond couldn’t provide for all of Moloka‘i, let alone all of Hawai‘i, but he does feed his family with the fish he farms. And when something goes wrong—a recent mudslide resulted in a baby-fish apocalypse— it teaches Ritte what his ancestors would have known but he has had to learn.

That’s how his vision went from restoring the fishpond to restoring the ahupua‘a, which in ancient Hawai‘i referred to a slice of land extending from the mountains down to the ocean. If the land above the pond had been properly irrigated, it could have prevented the mudslide that killed all those fish. And if everyone on Moloka‘i tended to their ahupua‘a the way their ancestors did, the island might in fact be able to dramatically reduce its reliance on imported food.

But over the years, Ritte said, the people of Hawai‘i got complacent. Too many forgot how to work hard, how to sweat and get dirty. Too few questioned what their changing way of life was doing to them. This is how they became “sitting ducks,” he told me, too willing to acclimate to a country that is not truly their own. “I am not an American. I want my family to survive. And we’re not going to survive with continental values,” he said. “Look at the government. Look at the guy who was president. And he’s going to be president again. He’s an asshole. So America has nothing that impresses me. I mean, why would I want to be an American?”

Ritte said he may not live to see it, but he believes Hawai‘i will one day become an independent nation again. “There’s a whole bunch of people who are not happy,” he said. “There’s going to be some violence. You got guys who are really pissed. But that’s not going to make the changes that we need.”

Still, change does not always come the way you expect. Ritte believes that part of what he’s doing on Moloka‘i is preparing Hawai‘i for a period of tremendous unrest that may come sooner rather than later, as stability in the world falters and as Hawaiians are roused to the cause of independence. “All the years people said, ‘You can control the Hawaiians, don’t worry; you can control them.’ But now they’re nervous you cannot control them.”

During my visit to Pu‘uhonua O Waimānalo, the compound that Dennis Kanahele and Brandon Maka‘awa‘awa have designated as the headquarters for the Nation of Hawai‘i, Maka‘awa‘awa invited me to the main office, a house that they use as a government building to hatch plans and discuss foreign relations. Recently, Kanahele and their foreign minister traveled to China on a diplomatic visit. And they’ve established peace treaties with Native American tribes in the contiguous United States—the same kind of treaty that the United States initially forged with the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, they pointed out to me.

These days, they are not interested in American affairs. They see anyone who works with the Americans, including Kūhiō Lewis and Brian Schatz, as sellouts or worse. To them, the best president the United States ever had was Clinton, because he was the one who signed the apology bill. Barack Obama may get points for being local—he was born and raised on O‘ahu—but they’re still waiting for him to do something, anything, for the Hawaiian people. As it happens, Obama has a house about five miles down the road. “I still believe that he’s here for a reason in Waimānalo,” Kanahele said, referring to this area of the island. “I believe the reason is what we’re doing.”

Outside, light rains occasionally swept over the house, and chickens and cats wandered freely. Inside was cozy, more bunker than Oval Office, with a rusted door swung open and walls covered in papers and plans. At one end of the room was a fireplace, and over the mantel was a large map of the world with Hawai‘i at the center, alongside portraits of Queen Lili‘uokalani and her brother King Kalākaua. Below that was a large humpback whale carved from wood, and wooden blocks bearing the names and titles of members of the executive branch. Another wall displayed a copy of the Kū‘ē Petitions, documents that members of the Hawaiian Patriotic League hand-carried to Washington, D.C., in 1897 to oppose annexation.

Kanahele is tall, with broad shoulders and a splatter of freckles on one cheek. He is thoughtful and serious, the kind of person who quiets a room the instant he speaks. But he’s also funny and warm. I’ve heard people describe Kanahele as Kamehameha-like in his looks, and I can see why. Kanahele told me that he is in fact descended from a relative of Kamehameha’s, “like, nine generations back.” Today, most people know him by his nickname, Bumpy.

The most animated I saw him was when I asked if he’d ever sat down with a descendant of the overthrowers. After all, it often feels like everyone knows everyone here, and in many cases they do, and have for generations. Kanahele told me the story of how, years ago, he’d had a conversation with Thurston Twigg-Smith, a grandson of Lorrin A. Thurston, who was an architect of the overthrow. Twigg-Smith was the publisher of the daily newspaper the Honolulu Advertiser, and Kanahele still remembers the room they sat in—fancy, filled with books. “I was excited because it was this guy, right? He was involved,” Kanahele said.

The experience left him with “ugly feelings,” he told me. “He called us cavemen.” And Twigg-Smith defended the overthrowers. I mentioned to Kanahele that I’d read Twigg-Smith’s account of the coup, in which he refers to it admiringly as “the Hawaiian Revolution.”

Twigg-Smith told Kanahele that his grandfather “did the best thing he thought was right at the time,” Kanahele said. When Kanahele asked, “Do you think that was right?,” Twigg-Smith didn’t hesitate. Yes, the overthrow was right, he said. Kanahele’s eyes widened as he recounted the exchange. “He thinks his grandfather did the right thing.” (Twigg-Smith died in 2016.)

Kanahele and Maka‘awa‘awa aren’t trying to bring back the monarchy. They aren’t even trying to build a democracy. Their way of government, outlined in a constitution that Kanahele drafted in 1994, is based on a family structure, including a council of Hawaiian elders and kānaka (Hawaiian) and non-kānaka (non-Hawaiian) legislative branches. “It’s a Hawaiian way of thinking of government,” Maka‘awa‘awa said. “It’s not democracy or communism or socialism or any of that. It’s our own form of government.”

Kanahele’s vision for the future entails reclaiming all of Hawai‘i from the United States and reducing its economic dependence on tourism and defense. He and Maka‘awa‘awa are unpaid volunteers, Maka‘awa‘awa told me. “Luckily for me and Uncle, we have very supportive wives who have helped support us for years.” Maka‘awa‘awa said that they used to pay a “ridiculous amount” in property taxes, but thought better of it when contemplating the 65-year lease awarded in 1964 to the U.S. military for $1 at Pōhakuloa, a military training area covering thousands of acres on the Big Island. So about eight years ago, they decided to pay $1 a year. The state is “pissed,” he told me, but he doesn’t care. “Plus,” he added, “it’s our land.”

I had to ask: Doesn’t an independent nation need its own military? Other than the one that was already all around them, that is. Some 50,000 active-duty U.S. service members are stationed throughout the Islands. Many of the military’s 65-year leases in Hawai‘i are up for renewal within the next five years, and debate over what to do with them has already begun. I thought about our proximity to Bellows Air Force Station, just a mile or two down the hill from where we were sitting. Yes, Kanahele told me. “You need one standing army,” he said. “You got to protect your natural resources—your lands and your natural resources.” Otherwise, he warned, people are “going to be taking them away.”

I asked them how they think about the Hawai‘i residents—some of whom have been here for generations, descendants of plantation laborers or missionaries—who are not Hawaiian. There are plenty of non-kānaka people who say they are pro–Hawaiian rights, until the conversation turns to whether all the non-kānaka should leave. “We think about that,” Kanahele said, because of the “innocents involved. The damage goes back to America and the state of Hawai‘i. That’s who everybody should be pointing the finger at.”

And it’s not like they want to take back all 4 million acres of Hawai‘i’s land, Maka‘awa‘awa said. “Really, right now, when we talk about the 1.8 million acres of ceded lands”—that is, the crown and government lands that were seized in the overthrow and subsequently turned over to the United States in exchange for annexation—“we’re not talking about private lands here. We’re talking strictly state lands.”

Kanahele calmly corrected him: “And then we will claim all 4 million acres. We claim everything.”

As I was reporting this story, I kept asking people: What does America owe Hawai‘i, and the Hawaiian people? A better question might be: When does a nation cease to exist? When its leader is deposed? When the last of its currency is melted down? When the only remaining person who can speak its language dies? For years I thought of the annexation-day ceremony in 1898 as the moment when the nation of Hawai‘i ceased to be. One account describes the final playing of Hawai‘i’s national anthem, by the Royal Hawaiian Band, whose leader began to weep as they played. After that came a 21-gun salute, the final national salute to the Hawaiian flag. Then the band played taps. Eventually all kingdoms die. Empires, too.

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom set in motion a series of events that disenfranchised Hawaiians, separated them from their land and their culture, and forever altered the course of history in Hawai‘i. It was also a moment of enormous and lasting consequence for the United States. It solidified a worldview, famously put forth in the pages of this magazine by the retired naval officer Alfred Thayer Mahan in 1890, that America must turn its eyes and its borders ever outward, in defense of the American idea.

But there were others who fought against the expansionists’ notion of America, arguing that the true American system of government depended on the consent of the governed. Many of the people arguing this were the abolitionists who led and wrote for this magazine, including Mark Twain and The Atlantic’s former editor in chief William Dean Howells, both members of the Anti-Imperialist League. (Other anti-imperialists argued against expansion on racist grounds—that is, that the U.S. should not invite into the country more nonwhite or non-Christian people, of which there were many in Hawai‘i.)

This was the debate Americans were having about their country’s role in the world when, in March 1893, Grover Cleveland was inaugurated as president for the second time. Cleveland, the 24th president of the United States, had also been the 22nd; Benjamin Harrison’s single term had been sandwiched in between. Once he was back in the White House, Cleveland immediately set to work undoing the things that, in his view, Harrison had made a mess of. Primary among those messes was what people had begun to refer to as “the question of Hawaii.”

After writing to Harrison in January 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani had sent a letter to her “great and good friend” Cleveland in his capacity as the president-elect. “I beg that you will consider this matter, in which there is so much involved for my people,” she wrote, “and that you will give us your friendly assistance in granting redress for a wrong which we claim has been done to us, under color of the assistance of the naval forces of the United States in a friendly port.”

Whereas Harrison, in the twilight of his presidency, had sent a treaty to the Senate to advance the annexation of Hawai‘i, Cleveland’s first act as president was to withdraw that treaty and order an investigation of the overthrow. Members of the Committee of Safety and their supporters, Cleveland learned, had seized ‘Iolani Palace as their new headquarters—they would later imprison Queen Lili‘uokalani there, in one of the bedrooms upstairs, for nearly eight months—and raised the American flag over the main government building in the palace square. Cleveland now mandated that the American flag be pulled down and replaced with the Hawaiian flag.

This set off a firestorm in Congress, where Cleveland’s critics eventually compared him to a Civil War secessionist. One senator accused him of choosing “ignorant, savage, alien royalty, over American people.”

By then, the inquiry that Cleveland ordered had come back. As he explained when he sent the report on to Congress, the investigation had found that the overthrow had been an “act of war,” and that the queen had surrendered “not absolutely and permanently, but temporarily and conditionally.”

Cleveland had dispatched his foreign minister to Hawai‘i, former Representative Albert S. Willis of Kentucky, to restore the queen to power. Willis’s mission in Honolulu was to issue an ultimatum to the insurrectionists to dissolve their fledgling government, and secure a promise from Queen Lili‘uokalani that she would pardon the usurpers. But the Provisional Government argued that the United States had no right to tell it what to do.

“We do not recognize the right of the President of the United States to interfere in our domestic affairs,” wrote Sanford Dole, the self-appointed president of Hawai‘i’s new executive branch. “The Provisional Government of the Hawaiian Islands respectfully and unhesitatingly declines to entertain the proposition of the President of the United States that it should surrender its authority to the ex-Queen.”

This was, quite obviously, outrageous. Here Dole and his co-conspirators were claiming to be a sovereign nation—and using this claim to rebuff Cleveland’s attempts to return power to the sovereign nation they’d just overthrown—all while having pulled off their coup with the backing of American military forces and having flown an American flag atop the government building they now occupied.

In January 1894, the American sugar baron and longtime Hawai‘i resident Zephaniah Spalding testified before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations about the situation in Honolulu. “We have now as near an approach to autocratic government as anywhere,” Spalding said. “We have a council of 15, perhaps, composed of the businessmen of Honolulu” who “examine into the business of the country, just the same as is done in a large factory or on a farm.”

The insurrectionists had, with support from the highest levels of the U.S. government, successfully overthrown a nation. They’d installed an autocracy in its place, with Dole as president.

Americans argued about Hawai‘i for five long years after the overthrow. And once the United States officially annexed Hawai‘i in 1898 under President William McKinley, Dole became the first governor of the United States territory. Most Americans today know his name only because of the pineapple empire one of his cousins started.

All along, the debate over Hawai‘i was not merely about the fate of an archipelago some 5,000 miles away from Washington. Nor is the debate over Hawai‘i’s independence today some fringe argument about long-ago history. America answered the “question of Hawaii” by deciding that its sphere of influence would not end at California, but would expand ever outward. Harrison took the aggressive, expansionist view. Cleveland took the anti-imperialist, isolationist one. This ideological battle, which Harrison ultimately won (and later regretted, after he joined the Anti-Imperialist League himself), is perhaps the most consequential chapter in all of U.S. foreign relations. You can draw a clear, straight line from the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom to the attack on Pearl Harbor to America’s foreign policy today, including the idea that liberal democracy is worth protecting, at home and abroad.

It’s easy to feel grateful for this ethos when contemplating the alternative. In the past century, America’s global dominance has, despite episodes of galling overreach, been an extraordinary force for good around the world. The country’s strategic position in the Pacific allowed the United States to win World War II (and was a big reason the U.S. entered the war in the first place). The U.S. has continued to serve as a force for stability and security in the Pacific in a perilous new chapter. How might the world change without the United States to stand up to Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin?

But to treat the U.S. presence in Hawai‘i as inevitable, or even as a shameful but justified means to an end, is to disregard the values for which Americans have fought since the country’s founding. It was the United States’ expansion into the Pacific that established America as a world superpower. And it all began with the coup in Honolulu, an autocratic uprising of the sort that the United States fights against today.

Perhaps the true lesson of history is that what seems destined in retrospect—whether the election of a president or the overthrow of a kingdom—is often much messier and more uncertain as it unfolds. John Waihe‘e, the former governor, told me that he no longer thinks about how to gain sovereignty, but rather how Hawai‘i should begin planning for a different future—one that may arrive unexpectedly, and on terms we may not now be considering.

Waihe‘e is part of a group of local leaders that has been working to map out various possible futures for Hawai‘i. The idea is to take into account the most pronounced challenges Hawai‘i faces: the outside wealth reshaping the Islands, the economic overreliance on tourism, the likelihood of more frequent climate disasters, the potential dissolution of democracy in the United States. One of the options is to do nothing at all, to accept the status quo, which Waihe‘e feels certain would be disastrous.

Jon Kamakawiwo‘ole Osorio, another member of the group, agrees. Osorio is the dean of the Hawai‘inuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Undoing a historic wrong may be impossible, he told me, but you have a moral obligation to try. “If things don’t change, things are going to be really fucked up here,” Osorio said. “They will continue to deteriorate.” (As for how things are going in the United States generally, he put it this way: “I wouldn’t wish Trump on anyone, not even the Americans.”)

Osorio’s view is that Hawaiians should take more of a Trojan-horse approach—“a state government that essentially gets taken over by successive cadres of people who want to see an end to military occupation, who want to see an end to complete reliance on tourism, who see other kinds of possibilities in terms of year-round agriculture,” he told me. “Basically, being culturally and socially more and more distinct from the United States.” That doesn’t mean giving up on independence; it just means taking action now, thinking less about history and more about the future.

But history is still everywhere in Hawai‘i. On the east side of Moloka‘i, I drove by a house that had a sign out front that just said 1893 with a splotch of red, like blood. If you head southwest on Kaua‘i past Hanapēpē, and then on to Waimea, you can walk out onto the old whaling pier and see the exact spot where Captain James Cook first landed, in 1778. Not far from there is the old smokestack from a rusted-out sugar plantation. All around, you can see the remnants of more than two centuries of comings and goings. A place that was once completely apart from the world is now forever altered by outsiders. And yet the trees still spill mangoes onto the ground, and the moon still rises over the Pacific. Hawaiians are still here. As long as they are, Hawai‘i belongs to them.

Over the course of my reporting, several Hawaiians speculated that Hawai‘i’s independence may ultimately come not because it is granted by the United States, but because the United States collapses under the second Trump presidency, or some other world-altering course of events. People often dismiss questions of Hawaiian independence by arguing, fairly, that if the United States hadn’t seized the kingdom, Britain, Japan, or Russia almost certainly would have. Now people in Hawai‘i want to plan for how to regain—and sustain—independence if the United States loses power.

Things change; Hawai‘i certainly has. All these years, I’ve been trying to understand what Hawai‘i lost, what was stolen, and how to get it back. What I failed to realize, until now, is that the story of the overthrow is not really the story of Hawai‘i. It is the story of America. It is the story of how dangerous it is to assume that anything is permanent. History teaches us that nothing lasts forever. Hawaiians have learned that lesson. Americans would do well to remember it.

This article appears in the January 2025 print edition with the headline “What Happens When You Lose Your Country?”