Just months ago, it seemed conceivable that Donald Trump might spend the final stretch of the presidential campaign in a Washington, D.C., courtroom, on trial for his efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 election. Even a week ago, it was possible that voters might head to the polls on Election Day with Trump’s sentencing in the New York hush-money case, then scheduled for September 18, fresh in their mind. But on Friday, New York Supreme Court Justice Juan Merchan pushed the sentencing date back until the end of November—meaning that Trump will go into the election as a convicted felon, but one whose punishment has not yet been decided. And in Washington, Judge Tanya Chutkan has set out a schedule revealing that the January 6 case will not be going to trial anytime soon.

For this, Americans can blame the Supreme Court.

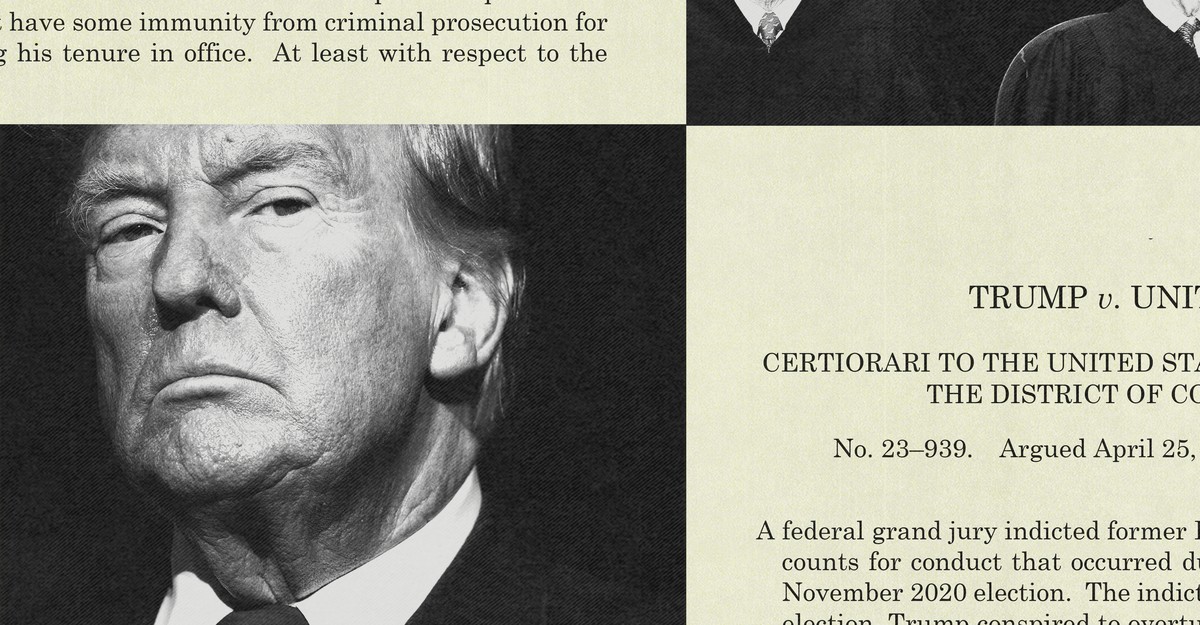

The cases against Trump in Georgia and Florida have foundered for their own reasons—in Georgia, poor judgment by the district attorney; in Florida, a judge appointed by Trump who has done everything in her power to upend the prosecution. But in both D.C. and New York, the culprit is the same: Trump v. United States, the Supreme Court’s controversial July ruling establishing broad presidential immunity from prosecution, was a victory for Trump beyond his wildest dreams, shielding him from full criminal accountability for his actions. But the decision by the Court’s right-wing supermajority wasn’t just a gift to Trump on the substance. It provided Trump with extensive room for delays, allowing him to push back key stages of the criminal process past Election Day.

Because Trump had appealed the issue up from Judge Chutkan, the Court placed proceedings in the January 6 case on hold for months while it pondered the issue—preventing the case from going to trial in March, as Chutkan had originally planned. And now Trump has managed to use the immunity ruling to delay sentencing in the New York case as well, even though a Manhattan jury found him guilty before the Court’s ruling. As both judges try to forge ahead, the true scope of the disruption caused by the decision is coming into focus.

Last Thursday, Judge Chutkan opened her courtroom doors for the first hearing in the January 6 case in almost a year. (“Life was almost meaningless without seeing you,” Trump’s counsel John Lauro jokingly told the judge.) The mood, my Lawfare colleagues Anna Bower and Roger Parloff described, was akin to what an archaeologist might feel examining the ruins of Pompeii: Here lies the January 6 prosecution, trapped in stasis. In this instance, though, Chutkan is tasked with determining which of Pompeii’s residents—that is, which components of the indictment—might be resurrected following the Supreme Court’s intervention.

That will be a difficult task. Because the decision in Trump has another major advantage for the eponymous plaintiff: It is very, very confusing. And confusion means even more delay.

The ruling divided presidential conduct into three categories: conduct at the core of the president’s constitutional responsibilities, for which he is absolutely immune; conduct entirely outside the president’s official work, for which he is not immune; and a muddy middle category of official conduct that is only “presumptively” immune, and which prosecutors may pursue if they can show that doing so would pose no “dangers of intrusion” on presidential power. Last month, Special Counsel Jack Smith unveiled a new iteration of the January 6 indictment tailored to the Court’s specifications, slicing out conduct that the majority had identified as clearly immune—specifically, Trump’s effort to leverage the Justice Department to convince state legislatures that the election was stolen.

So far so good. But quagmires remain. The new indictment largely retains material related to Trump’s pressure campaign on then–Vice President Mike Pence to upend the electoral count on January 6—which makes sense, given that the Court placed Trump’s conversations with Pence in the “presumptively immune” category. How, though, is Chutkan to decide whether the prosecution has cleared the bar to rebut that presumption? For that matter, how is she to identify the fuzzy line between unofficial and official conduct? The Supreme Court has provided precisely no guidance. According to a scheduling order that Chutkan released following last week’s hearing, the briefing alone on the immunity question will take until October 29, six days before the election. And, importantly, because the Court also indicates that Trump can immediately appeal any decision from lower courts on these questions—what’s known as an “interlocutory appeal”—whatever Chutkan does could well be subject to months and months of additional litigation.

Trump v. United States is “subject to a lot of different readings,” Chutkan noted drily at one point during the hearing. At another, she commented that she was “risking reversal” from the Supreme Court “no matter what I do.”

So, too, is Justice Merchan. The true, absurd scope of the complications caused by the immunity ruling is perhaps most apparent in New York, where the Supreme Court’s decision has called into question aspects of a prosecution that has nothing to do with presidential power at all. The facts of the case involved a scheme by Trump and those around him in the run-up to the 2016 election to bury negative news stories about the candidate’s past extramarital dalliances, and then to fudge records to conceal those payments. Much of the conduct at issue took place before Trump was ever in office, and the portion that touched on Trump’s time as president involved his efforts to hide the hush-money scheme after the fact—not precisely an example of the chief executive carrying out his oath to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution.

It is impossible to argue with a straight face that this comes anywhere near the realm of official presidential conduct, and the Supreme Court didn’t even try. What it did instead was something far more slippery. In perhaps the most baffling section of the Court’s ruling, the majority held that not only are prosecutors to avoid bringing charges against a former president for the expansive category of official acts, but even evidence of official acts can’t be used to prosecute unprotected conduct—unless the government can point to a “public record” of the official act instead. (This portion of the immunity decision went too far for Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who wrote separately that such a rule would “hamstring the prosecution.”) Precisely what this means is—yet again—unclear, but Trump pounced, moving quickly to inform Justice Merchan that the district attorney had relied here and there during the trial on material from Trump’s time in the White House that implicated his responsibilities as president. For this reason, Trump argued, his conviction should be thrown out.

This set in motion the chain of events that ultimately led to the delay of Trump’s sentencing into late November. Merchan had originally scheduled the sentencing for July 11—just 10 days after the Court handed down its opinion in Trump. The back-and-forth of court filings between Trump and District Attorney Alvin Bragg over the immunity question led Merchan to delay the date first to September 18, and then—on Friday—again, to November 26. “We are now at a place in time that is fraught with complexities rendering the requirements of a sentencing hearing … difficult to execute,” the judge explained in announcing the most recent delay, referring to the upcoming election.

Many commentators were critical of Merchan’s decision. “The legal system was cowed by Trump’s bullying and lawlessness,” Greg Sargent declared in The New Republic. Perhaps anticipating such a response, Merchan’s letter pushing back the hearing has a somewhat defensive tone, insisting that the New York court “is a fair, impartial, and apolitical institution.”

Moreover, Justice Merchan was in a genuinely tight spot here. Resolving Trump’s immunity motion requires untangling a snarled knot of questions on which the Supreme Court offered little clarity. How exactly is the judge to determine whether the evidence in question—such as testimony by Hope Hicks about Trump’s conversations with her during her time in the White House press office—really does implicate official acts, or whether it’s unofficial conduct? If the conduct is presumptively immune, has the district attorney done enough to rebut that presumption? Even if it is official, could the conviction survive, or is any use of evidence concerning immunized conduct such an egregious violation that the verdict must be overturned, as Trump argues?

And, crucially, does the Court’s seeming guarantee of an interlocutory appeal for Trump on these immunity issues apply to evidentiary questions like these—meaning that Trump could immediately appeal any unfavorable ruling by Merchan, potentially sending it back up to the Supreme Court? Nobody knows, but the additional time it would take to hash out that question could have meant that even if Merchan had tried to speed proceedings along, sentencing would never have happened before Election Day regardless. Seemingly in recognition of this fact, the district attorney’s office didn’t object to Trump’s request to delay the sentencing hearing. That choice limited Merchan’s ability to move forward with sentencing without opening himself up to charges of politicizing the proceedings in order to damage Trump. (Seemingly unsatisfied with Merchan’s decision, Trump is now asking the federal courts to delay the case still further while he litigates the immunity question.)

For those who hoped that Trump might finally face criminal accountability before the election, this is a frustrating dodge—another example of the legal system’s apparent inability to hold Trump responsible for his actions. But the real villain here isn’t Bragg or Merchan, who are doing their best to carry out justice under difficult circumstances. It’s the Supreme Court, which created an unmanageable situation that played directly into Trump’s goal of delaying a legal reckoning. The conservative supermajority seemed genuinely troubled by Trump’s allegations of unjust persecution by prosecutors and lower courts, but comparatively unconcerned about the risks to democracy posed by Trump’s own actions.

If Trump wins the election, the expectation is that he’ll order the Justice Department to dismiss the federal cases against him. His sentencing in New York, meanwhile, could be put on hold indefinitely. If he loses, the litigation over immunity seems certain to stretch both cases out for months, if not longer.

None of this was preordained. The Supreme Court didn’t need to take up the immunity case to begin with. Once it did, the overwhelming majority of experts and commentators—myself included—expected that, at most, the Court would fashion a rule carving out some limited category of immunized conduct, perhaps creating difficulties in the January 6 case but certainly not creating problems in New York. Instead, the conservative justices issued a ruling that not only established a sweeping and poorly defined immunity but also created so many avenues for challenge and confusion that the Court functionally collaborated in Trump’s strategy of delay.

Perhaps this reading is uncharitable to the Court—but at a certain point, charity is no longer merited. Following the immunity ruling, President Joe Biden announced support for a slate of reforms pushing back against the Court’s decision and advocating changes to an institution that has become extreme and unaccountable. Should Kamala Harris triumph in November, the recent delays in New York and D.C. are further reasons to take up the cause of Court reform again.