Andy Warhol is one of the most prolifically quoted artists. Yet the truth behind an oft referenced remark is heavily debated. The phrase “I want to be a machine” has been used in papers exploring the artistic desire for automation and even for the title of a 2018 exhibition and book produced by The National Galleries of Scotland. The show placed Warhol’s work in juxtaposition with Eduardo Paolozzi, claiming that the artist’s original comment reflected upon a “serious belief that art would become increasingly mechanised”. But did he ever say it?

The quote is rooted in a 1963 conversation between Warhol and writer-curator Gene Swenson. It was published by ARTNews for a series titled ‘What is Pop Art? Answers from 8 Painters’, which also featured interviews with Jim Dine, Robert Indiana and Roy Lichtenstein.

The series came to define the burgeoning movement to some degree, with critic Lucy Lippard claiming Swenson was a highly trusted source for artists. The accuracy of these interviews was not questioned, until professor and author Jennifer Sichel began to research the source of this particular Warhol quote when The National Galleries of Scotland show opened.

As luck would have it, the only surviving tape of the interview series is the one between Swenson and Warhol, and it paints a very different picture. It appears that the artist never spoke about wanting to be a machine because of its potential for creative automation. This quote does, in fact, stem from Swenson’s early question, “What do you say about homosexuals?”

Sichel noted that the iconic pop artist’s response is full of “great care and complexity”. His comment about being a machine was phrased, “I think everybody should be a machine,” followed by, “I think everybody should like everybody”. He was reflecting on his belief that we should be less judgemental and more open to queer attraction, lacking the rigid value judgements associated with humanity and instead on the moral neutrality of machines, leaving us open to freely follow our desires and let others do the same.

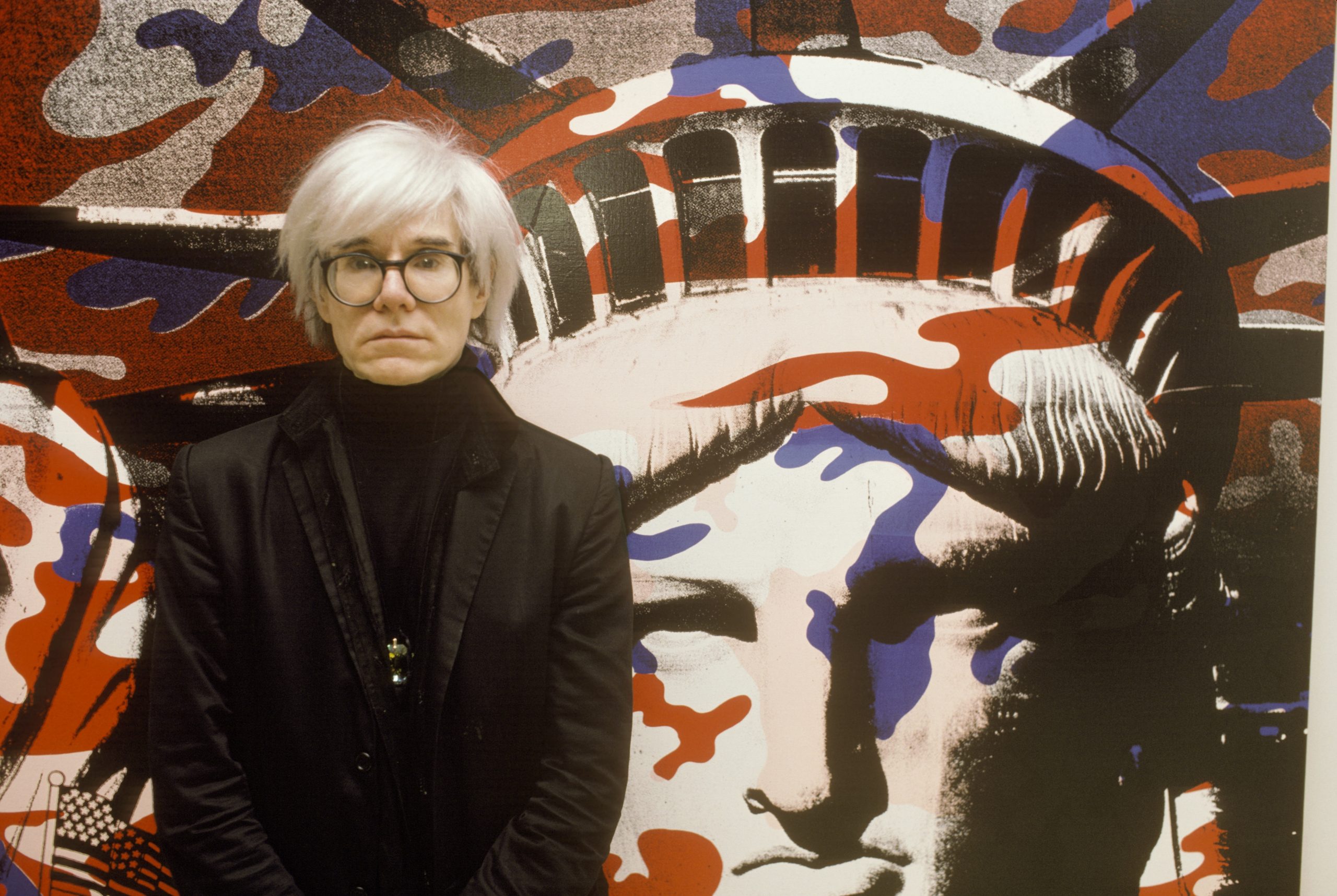

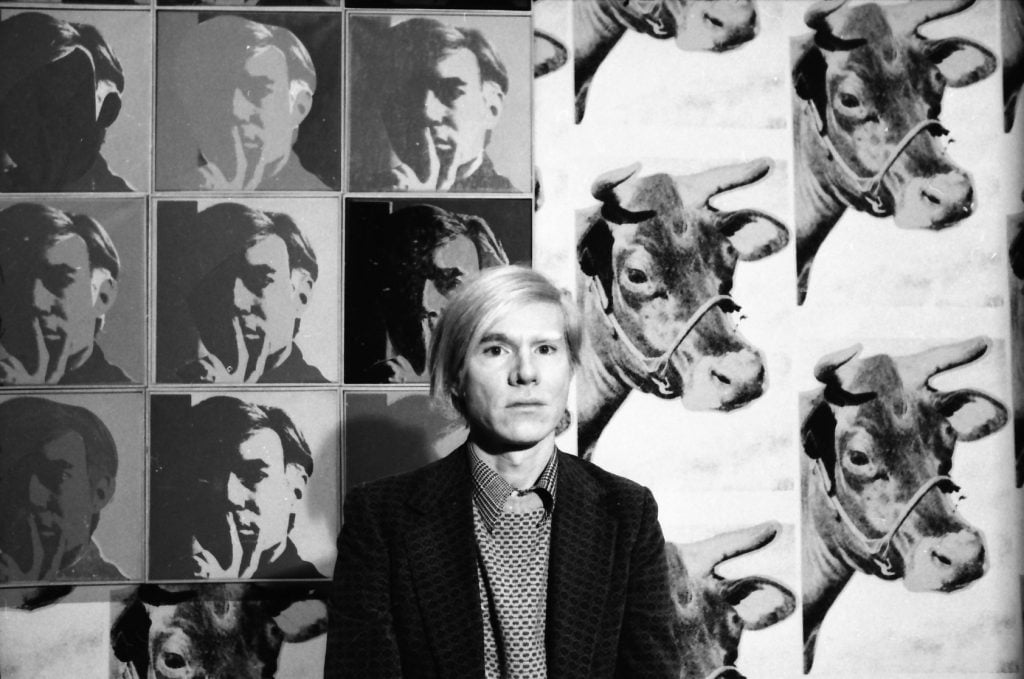

Andy Warhol at his May 1971 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. (Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images)

At one point in the recording, Warhol is heard declaring “I think that the whole interview on me should be just on homosexuality.” But ultimately Swenson’s original question, and the context of its answer, were slashed from the final piece. The comments about machines remain, with no mention at all to homosexuality. So why was this part removed?

Within the tape, Sichel discovered a later recorded conversation between Swenson and the artist Joe Raffaele, which seems to suggest that the magazine’s editor, Tom Hess, heavily changed the final transcript. In the following years, Swenson would enter numerous battles with publishers and institutions over their suppression of conversations about queerness in the arts. Sichel also suggests that Hess experienced a great deal of backlash from other writers and artists for his ruthless input, with Donald Judd suggesting he could completely changed the meaning of an interview through his edits.

So Warhol’s words went into the final piece, but detached from their original conversation. The artist’s queerness was often ignored or underplayed in his lifetime, and while Swenson was more assertive in his calls for open dialogue around homosexuality, he wasn’t able to get this part of their conversation into the final piece.

“Warhol constructed his ‘fantasy’ about everybody being a machine and liking everybody explicitly as a ‘kind of different’ strategy to speak on the record about homosexuality in a fantastical way that could be generative, open, and ambiguous—or, in a word, queer—indeed confirms what scholars have long surmised,” Sichel wrote in her research, “that even as Warhol’s work addresses consumerism, serial production, and modernist myths of authenticity and creativity, it is also and fundamentally about queer ways of feeling and being in the world.”